26 February 2019 || 7 minute read

The 31st UKSEDS National Student Space Conference was held in Edinburgh on 2 & 3 March 2019, the first time it had visited Scotland, and to open the conference I gave a State of the Nation keynote on the status of the Scottish space sector. This article builds on that to examine the challenge of actually achieving the Scottish government supported growth targets for the sector.

So what is the state of the nation’s space sector? Well, the conference was sold-out. So that’s a good start! In Scotland today there are over 130 organisations that are part of the space sector, up 27% since 2016. However, this is more or less in-line with what you might expect on a pro-rata basis for the UK’s space sector; about 9% of UK’s space organisations for about 8% of the UK’s population.

Where Scotland really punches above its weight is in employment, with over 7500 space jobs, up 9% since 2016 and up 38% since 2014.

In other words, 18% of all UK space jobs are in Scotland, giving Scotland the highest density of space jobs in the UK with 0.29% of the workforce in the space sector, against a UK average of 0.13%.

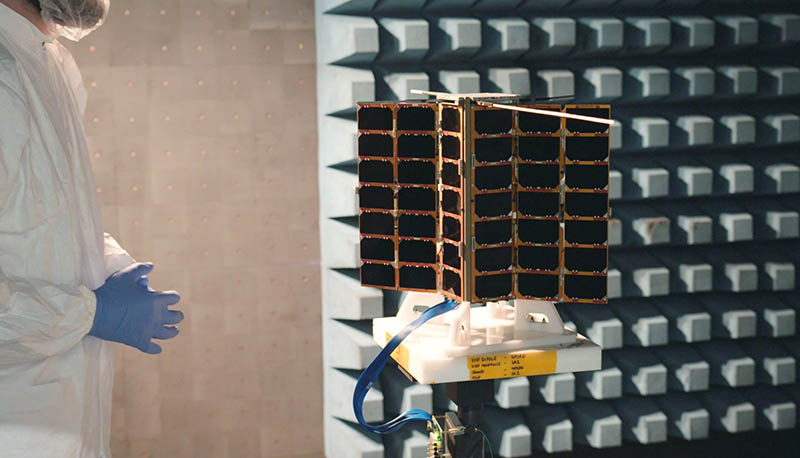

Today, Scotland builds more spacecraft than anywhere else in Europe and aims to host the first spaceport in Europe. Through to the end of 2018, Spire alone have built 95 spacecraft in Scotland, with 72 still in orbit, all operated from Scotland. In 2018 Spire launched 28 satellites, all built in Scotland.

But, it’s not just about the spacecraft that Clyde Space, Alba Orbital, and Alba OrbitalAlba Orbital build. After all, the spacecraft is only as valuable as the data or service it provides.

- Spire are a data analytics company, who just happen to build spacecraft.

- Bird.i are using space-derived intelligence to monitor global construction.

- Trade in Space are developing new financial services with data collected by satellites, making peer-to-peer trading fairer & easier.

- Ecometrica, GSi, Carbomap, and others are monitoring the Earth’s forests and crops.

- Astrosat are helping people understand the planet, whilst aiding disaster response.

- SoXSA are helping to developing smart, connected fish farms.

- Huli are using space-derived intelligence to plan your outdoor adventure.

- And, thanks to Space Horizons we even have a card game about space!

Scotland has a thriving entrepreneurial environment. In the last three years, 28% of UK university spin-outs come from Scotland; compared to 18% in London. And what of those space start-ups? Well, an average start-ups in the Tontine incubator increases turnover by £126k and two employees, a great performance.

Space start-ups on average increase turnover by £274k and four employees.

Tontine lane, with view of the Tontine Incubator.

Tontine lane, with view of the Tontine Incubator.

But, it’s not just about entrepreneurship, job, and company creation. Scotland has a vibrant, internationally recognised, and job creating academic and research community that works in partnership to create the pipeline of World class ideas and talent that the sector needs.

Scotland is at the forefront of space science with, for example, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s MIRI (Mid InfraRed Instrument) camera and spectrometer being developed in Scotland, whilst we also lead the development of gravitational wave research through both the LISA-pathfinder (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna) and LISA missions.

Recognising the clear strength of the sector, a government supported growth target of 1% of the global space economy by 2030has been adopted. Scotland has 0.07% of global population. This is a target of £4Bn per year, with an interim target of £570M by 2020, and excludes direct-to-home (DTH) broadcast, in other words, satellite television from Sky.

The exclusion of DTH broadcast is likely sensible as this is, at best, a mature market with limited growth potential. However, the inclusion of DTH broadcast in the above space sector size and health statistics obscures the scale of this stated ambition.

Of the 130+ space organisations in Scotland only 83 have their headquarters in Scotland. This is up 24% since 2016, but actually a 1% reduction in Scottish space organisations with a Scottish HQ. From those 83 HQ’s, the Scottish sector generates a revenue of £140M per year, up 7% since 2016. This revenue figure is lower than otherwise expected as large UK and multi-national organisations that are headquartered elsewhere have a strong presence in Scotland.

Removing DTH broadcast from the Scottish figures is challenging. However, Sky employ around 29000 people worldwide, with 23000 of them listed on LinkedIn, approximately 80%. Of those in LinkedIn, around 2500 are located in Scotland. As such, Sky’s Scottish workforce can be guesstimated at around 3125, assuming a similar 80% representation on LinkedIn.

Consequently, non-DTH broadcast Scottish space employment can perhaps be guesstimated at around 4500 jobs. Of note, this would suggest that Scottish DTH broadcast jobs, which have been broadly steady since 2014/15 are masking growth in non-DTH broadcast jobs, which would appear to be up around 10%.

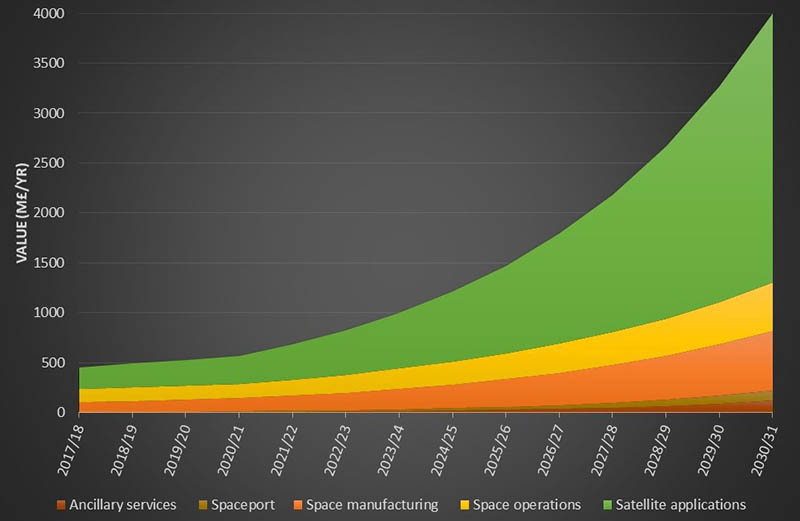

The value of the Scottish space sector is far more challenging to guesstimate as it is likely more than the £140M in revenue from Scottish headquartered organisations. A crude estimate can perhaps be gained by assuming each job ‘costs’ £100k per year, a standard costing rule of thumb, giving a sector value of around £450M per year in FY2017/18. As such, to achieve the interim growth target a year-on-year growth rate of 8–9% is required through to 2020.

Beyond 2020, an annual growth rate of 20–23% is required to achieve the £4Bn per year target by 2030.

The interim target appears ambitious but achievable based on recent growth rates. However the 2030 target would appear more challenging without significant new investment and restructuring of the Scottish sector.

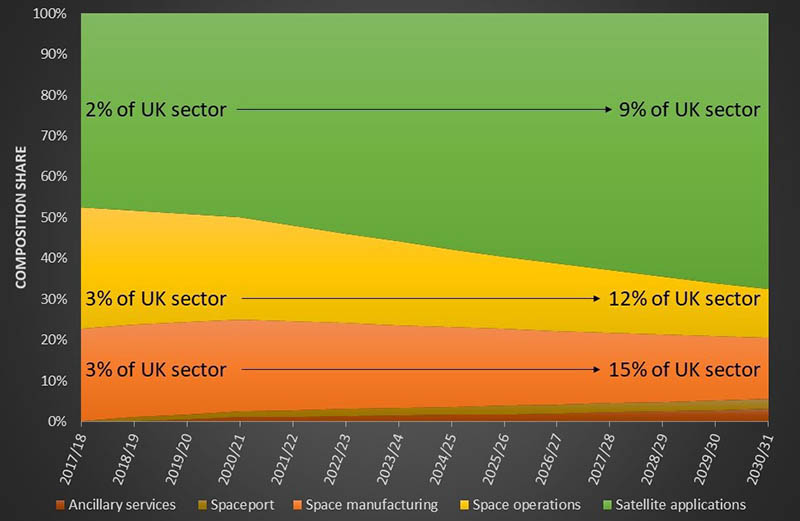

The composition of the Scottish space sector excluding DTH broadcast is difficult to accurately state. However, a 2016 report by London Economics suggested the sector could be sub-divided as 23% Space Manufacturing (3.5% of the UK sector), 33% Space Operations (3.1% of the UK sector), and 44% Satellite Applications, excluding DTH broadcast, (2.1% of the UK sector), and 0% Ancillary Services and Spaceport.

The number of ways to restructured the sector is of course innumerable, but I’ll present one possible scenario that recognises the already committed UK investment into creating a spaceport, and I’ll assume that spaceport is in Scotland.

The addressable market for a UK Spaceport was estimated by Frost & Sullivan’s 2018 UK Spaceport Business Case Evaluation at $5.5Bn (£4.4Bn) between 2021–2030, with in-year values towards the end of that period being as high as $700M (£560M). If the UK captures around 20% of that addressable market, and the vast majority of that is attributed to Scotland then the spaceport could be, directly, worth around £100M per year by 2030 to the Scottish space economy. It is also likely that spin-off benefits would occur in other parts of the sector, increasing this value.

Comparing the structure of the Scottish and UK sectors it is apparent that the Scottish sector is currently much more reliant on manufacturing and operations, and much less on satellite applications. Note that the UK-wide space manufacturing and space operations sectors are each thought to be worth around £4Bn per year by 2030. Hence achieving the Scottish target through investment in these sectors alone is likely to be unrealistic.

The below graphs shows one possible restructuring scenario achieved through investment across the sector, led and informed by the satellite applications service and data value. After all, the spacecraft is only as valuable as the data or service it provides.

In this scenario growth in manufacturing of around 17% per year, and operations of around 13% per year in the period from 2020–2030 are required such that both become proportionately greater than a UK pro-rata level by 2030. Meanwhile the growth in Satellite Applications is to the UK pro-rata level by 2030, requiring an annual growth rate of 25% in the period from 2020–2030, while ancillary services grow to around 3% of the Scottish sector, a similar level to that of the UK-wide sector, generating around £120M per year in this scenario.

These growth rates make the Scottish government supported growth target of 1% of the global space economy by 2030 somewhat ambitious, and show a clear need for significant targeted investment if the potential that has been recognised is to be realised.